Key Links: Everyday Rail English and Key Events in China | Bilingual Rail Services

In early 2012, it took the best part of all day to get from Beijing to south-eastern China – a fact emphasised by the availability of High Speed train with sleeping cars between of Beijing and Fujian.

When the train manager of services D365 and D366 approached David to ask him to create a bilingual service card on the basis of a Chinese-only draft, little did either see that this was going to be the start of a decade-long engagement in improving passenger rail English services for China.

Today, David has moved way beyond these cards as English for Chinese railway passenger service were institutionalised and formalised in a standardisation push across all of China. In late 2017, he published, along with the China Railway Publishing House, the first formalised Everyday Rail English service booklets for members of rail staff across across China. Five years later, his norms were taken as definitive for training staff both onboard and at stations serving the Beijing 2022 Winter Games.

As Told in Person by David…

I have noticed “funnyglish” across the Chinese rail network since Day 1 — a slightly wordy Caution, Risk of Pinching Hand made me look at the sticker a little funny. By 2012, I had amassed quite a collection of rail Chinglish: Artificial Ticket Office (for “ticket counters”), Caution, Scald Burns (for “Warning! Hot”), and the worst amongst the worst — Stop Mouth (for “entrance to platforms”).

I thought it was hilarious to snap away and to post them online, giving everyone quite a guffaw. However, that was where the fun stopped, since there was no way to correct them, even though I could guess what they probably meant. The signs were to be dreaded by many a lost expat, since none could really make head or tail of just exactly what they were on about, and could potentially cause travellers to miss their connections!

Hence, in early 2013, I decided to take things into my own hands and launch Everyday Rail English on Sina Weibo. (Just a few years earlier, I had started trialling translations.) The idea was to post at least one Weibo post telling people what the correct English was for most situations when dealing with passengers travelling by rail.

It begot itself a life of its own. Within two months, I had gone outside of Beijing to deliver my first lesson in proper rail English to others, and around this time, even Chinese national railways had started to take an interest. The official national railways newspaper site, peoplerail.com.cn, invited me to take up a position at their site to disseminate the good stuff even further, so I became a Rail English columnist. This was followed by appointments by stations in Xuzhou and Ji’nan in eastern China as their official Rail English consultant, which is why you should be seeing signs that don’t suck — or contain indecipherable Chinglish on them!

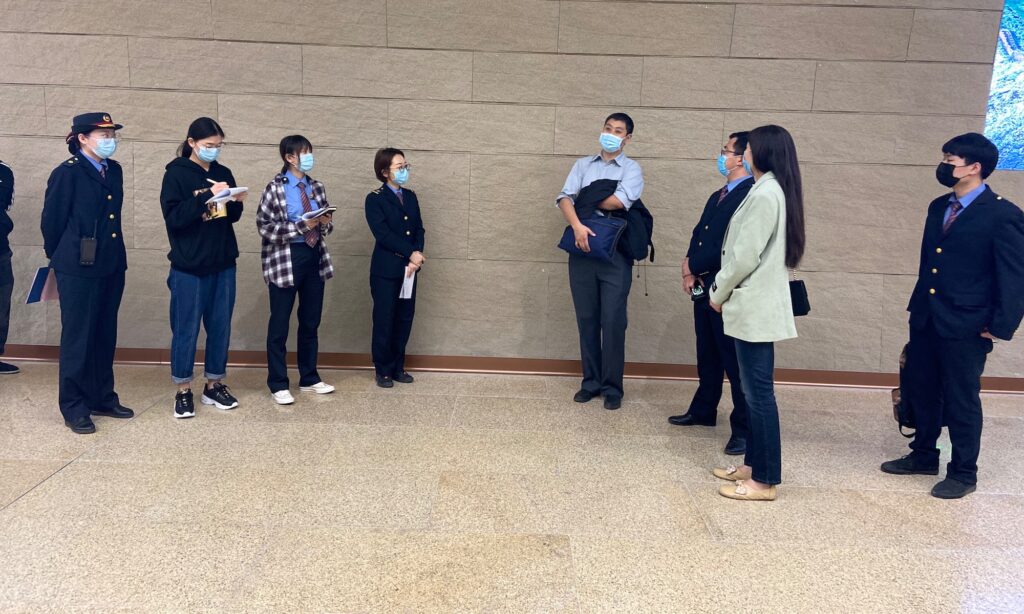

My Rail English lessons usually last 90-100 minutes (condensed versions are 50-60 minutes long) and is done pretty much in one go, but remains highly interactive. Rail crew are briefed on a bit about the English language and its use, how not to use English the wrong way, plus an overview of the terms station management staff have informed me they are having particular issues with. For around 40-50 minutes, crew are made clear the basic essentials about the English language, how expats think, plus the fundamentals of proper Rail English. Since late 2017, all lessons have also included an interactive element, especially when speaking to rail crew. It’s not a magic potion, but it’s hoped it can help these people — certainly until the next such lesson! For 2023 and beyond, I’m going to be making a significant changes to the lessons, so content learned will “stick” more, and be made more relevant for rail crew.

Everything I do with Everyday Rail English is based upon an entirely new bilingual database that I have built. This was after going to thousands of mass transit and national railway stations in over a dozen countries. This was basically something I started from scratch. All railway stations in China would in future be taught from this new unified database only. This also solves a key issue where the wordings used in different signs varied depending on who ran the station.

In 2018, the Everyday Rail English books I authored and published at the China Railway Publishing House in essence took things to a new level, as there was finally an officially published, tangible norm of proper English translations for the entire network. There are plans to launch a similar series of books for the city metro (urban rail) / light rail / tram network, as they seem to make logical, green connections.

I’d like to make it clear that I am not an official, salaried member of China Railways. However, we work together flexibly and in the interest of the greater good, in particular for international passengers. It has been my personal interest and incentive since childhood to ensure that when a new languages learned, it is used as accurately as possible. China runs a fantastic Green rail network, and I believe I’d like to give back to this one-of-a-kind network by combining my interests, knowledge, and support, to the benefit of the railways, but also to the travelling public.

I have yet to publish an official set of norms and standards in the way they are done by official government bodies, and as a lot of bureaucracy may well be involved in this, exclusively awaiting its realisation would delay improvement — not good for the railways. However, the Everyday Rail English content I make public — be in it in the form of books, lessons, or other Web-based content — are usually regarded as authoritative and optimised for use across the network. No rail organisation is forced to use them, of course, but most agrees that they are of the calibre that, if used, would help passengers get from A to B easier.

Results

Increasingly, David’s Everyday Rail English efforts are part of the Chinese national railway network, and are making travel easier for visitors and expats alike.

Ji’nan West railway station

All managed stations rolled out bilingual travel and safety information on info displays at platforms. Information provided helped passengers new to the station find exits, train connections, as well as ensure platform safety.

Beijing-Shanghai HSR Trains

On a number of trains between Beijing and Shanghai, passengers travelling over at Spring Festival were provided with a printed brochure which offered them information about faster or direct trains (and their times and/or stops served), Metro/Subway transfers (and timetables), and basic safety information.

China Railway Shanghai Trains

On in particular sleeper trains operated by trying to CR Shanghai, announcements were made (based on the standardised text in Everyday Rail English books) which informed passengers about special seating arrangements which may sometimes apply in sleeper carriages.

Beijing-Zhangjiakou HSR

David was one of the key participants in standardising English used both onboard trains and at stations. Significant improvements includes mandating that as many displays showed bilingual content (instead of just content in Chinese), developing Badaling Great Wall station’s scrolling information displays on the long “down” escalator for passengers taking trains (with special requirements on the timing and length of text displayed), and insuring that stations impose Beijing and nearby Hebei, as well as station and onboard crew, use the same norm of English. This series of effort was made for the Beijing 2022 winter Olympics. Unfortunately, due to Covid-19, its actual effect of helping members of the public were highly limited.

Qingdao stations

Through both training staff and improving actual signage at Qingdao and Qingdao North stations, passengers were able to find where they wanted to be faster. In particular, Priority Care Centres for passengers needing assistance, as well as specific ticket counters offering certain types of ticketing services, were translated into English accurately. (For example, only designated ticket counters offered refunds, or helped with passengers missing valid ID.)

Big on quality for big-ticket events

David has been deeply involved in perfecting Rail English for in particular the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics. For the first time ever, both onboard and station crew from China Railways (managing stations in both Beijing and Hebei) and Beijing Subway crew used the same norm of English, especially in taught lessons.

David has also been involved in teaching Rail English in time for the Hangzhou Asian Games, originally scheduled for 2022, but delayed by a year due to Zero Covid.

Action! Where David has taught or conducted Rail English quality inspections…

This list is presented in alphabetical order.

* = As part of a “multi-station lesson”. ** = Inspections only.

- Beijing Railway Station**

- Beijing North Railway Station**

- Beijing South Railway Station

- Beijing West Railway Station**

- Cangzhou West Railway Station*

- Changsha Railway Station**

- Dezhou East Railway Station*

- Gaomi Railway Station*

- Hangzhou Railway Station*

- Hangzhou East Railway Station*

- Hangzhou South Railway Station*

- Hangzhou West Railway Station*

- Huishan Railway Station*

- Jiande Railway Station*

- Ji’nan Railway Station

- Ji’nan East Railway Station**

- Ji’nan West Railway Station*

- Kunshan South Railway Station*

- Luoyang Longmen Railway Station

- Nanjing South Railway Station

- Nanning Railway Station

- Nanning East Railway Station

- Qiandaohu Railway Station*

- Qingdao Railway Station*

- Qingdao North Railway Station*

- Qingzhou City Railway Station*

- Qinhuangdao Railway Station

- Qufu East Railway Station*

- Shijiazhuang Railway Station**

- Suzhou Railway Station*

- Suzhou North Railway Station*

- Suzhou Industrial Park Railway Station*

- Taian (Shandong) Railway Station*

- Taiyuan Railway Station**

- Tengzhou East Railway Station*

- Tianjin Railway Station**

- Tianjin West Railway Station*

- Weifang Railway Station

- Wuxi Railway Station*

- Wuxi East Railway Station*

- Wuxi New District Railway Station*

- Xi’an North Railway Station*

- Xuzhou Railway Station*

- Xuzhou East Railway Station*

- Zaozhuang Railway Station*

- Zhuozi East Railway Station

Media reports

David is happy to report there has been a visible improvement that is gradually taking shape across the Chinese railway network as a result of these involvements. It started when Wuxi East station introduced bilingual signage that had no grammatical errors, and since then, stations across the nation have seen key improvements due to them using the new recommended standards.

Here’s what they say…

“It’s obvious that Dr Feng understands China’s railway system fully.”

Railway officials at Nanning Railway Station, as cited by Xinhua Guangxi (2014)

This morning, staff from the Beijing Speaks Foreign Languages office reported that English-language translations on public signs do not as of yet have a unified standard. […] Staff also were appreciative of Mr Feng and what he was doing. “He has contributed to society and large and has also been of service to everyone.”

Citing staff from the Beijing city government’s arm for English-language translations on public signs in a report by Legal Evening News, Beijing (2013)

[David Feng] translated recent railway policies on ticket replacement into English, to solve issues international passengers might have. […] There are people in society like David Feng who are making efforts by helping travellers from overseas. China’s official railway authorities should also consider if in more and more of China’s stations, there should be more guidance in English, so to make their journey smoother. Yesterday, Beijing South Railway Station, a major HSR hub, reposted David’s translations.

Report from the website of the influential Beijing Youth Daily (2012)

Looking into the future…

The number of international passengers dropped sharply in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, and in particular throughout 2022, when significant numbers of expats left China, frustrated by random lockdowns under extreme Zero Covid diktats.

The calamitous and failed Zero Covid policies were abandoned in late 2022 and early 2023, when the country reopened its borders. Also in early 2023, China Railways refreshed its Conditions of Carriage for the e-ticketing era and beyond.

In 2023, David intends to completely revamp Everyday Rail English to ensure it remains relevant for the present day — but also to futureproof developments which may happen in future.